Christmas in the trenches | December 1944

This post is also available in:

Nederlands

Nederlands

In the lead-up to operation ‘Veritable’ on February 8, 1945, Canadian troops in the Netherlands experienced a relatively calm winter. However, the Christmas Eve of 1944, amid patrols and small attacks, revealed an unexpected aspect of war: a moment of humanity and unpredictable events that changed the character of the front.

The harsh conditions at the front

In November 1944, after the Battle of the Scheldt, the Canadian 1st Army took over a significant portion of the front sector from the British 2nd Army. This extended the Canadian front line to over two hundred kilometers. In the ensuing months, Canadian soldiers had to withstand fierce German counterattacks, artillery bombardments, and the hardships of unfavorable weather. The static front in the Netherlands was marked by severe weather, with weeks of rain in October and November, followed by a harsh winter that hadn’t been seen in years. Despite these difficult conditions, soldiers eagerly looked forward to the annual Christmas dinner, a tradition where officers served their subordinates on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day. However, the German offensive in the Ardennes repeatedly postponed the Christmas dinner as units were put on high alert or had to move immediately to the front.

The Canadian soldiers Jim Hines, Harvey Hunter, and George Sporbeck of the Black Watch near their trench in Groesbeek on February 3, 1945. © Library and Archives Canada.

Amidst the icy cold and the tensions of war, Canadian soldiers tried to bring a touch of warmth and humanity to the harsh conditions at the front. Despite the hardships and the danger surrounding them, many managed to create a sense of camaraderie and solidarity on this festive evening. Candles were lit in makeshift shelters, and improvised Christmas decorations were hung. Soldiers shared their meager supplies, attempting to create a festive atmosphere amidst the harshness of war. For many, it was a moment of reflection, letting their thoughts drift to loved ones at home and the peace they hoped to restore.

For many, it was a moment of reflection, letting their thoughts drift to loved ones at home and the peace they hoped to restore.

Christmas at the front

Canadian soldiers would remember Christmas 1944 as a day when a kind of truce seemed to prevail on their side of the front. In the morning, the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade received reports from the Royal Regiment of Canada that German troops in nearby trenches were singing Christmas carols from their front positions. At the front of the 3rd Infantry Division, Lieutenant Donald Pierce, accompanied by a platoon of the North Nova Scotia, documented the unprecedented events in his diary, later forming the basis for the book “Journal of a War” (1965).

The crew of the Essex Scottish Regiment at a mortar position near Groesbeek on January 24, 1945. © Library and Archives Canada.

“Nowhere a sound, no shot. I strongly feel like I can see silence,” wrote Lieutenant Pierce. “The river, clearly visible beyond the icy field, carries a few drifting branches, and the snowflakes falling slowly are the only things in motion.” This unusual day of calmness and serenity seemed to have influenced both sides of the conflict. “A few minutes ago, I was sure I could hear the snowflakes falling on my battle jacket. A shout would be heard for miles. I have never seen such silence,” added Lieutenant Pierce.

On the frontline, it seemed as if both the Allies and German troops had decided to call off everything, as if this day rose above the horrors of war. It was an unexpected day of unity and brotherhood, where silence spoke, and peace, albeit temporarily, spread across the battlefield. According to the War Diary of the Calgary Highlanders, they were surprised on Christmas Eve by German frontline troops playing accordion and horn. A symphonic gesture that was answered with a salvo of rifles, Stens, Brens, grenades, and mortars from the Canadian side.

However, something special happened on Christmas Day: ‘Brigadier General Megill visited our four companies, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel R.L. Ellis, and wished all the men a Merry Christmas. It amused them both to hear that the Germans had treated our men to Christmas carols the previous evening, including Jingle Bells, Holy Night, and ended the concert with our national anthem, Oh Canada… At 6:00 p.m., Sergeant Major Vince Bowen took our bagpipers to the trenches of D Company to treat the Germans, in turn, to Christmas music.’

Crew members of a tank from the British 4th Battalion of the Royal Tank Regiment of the 4th Armoured Division unwrap a Christmas package. The tank is decorated as a “mobile Christmas tree.” © Imperial War Museum

Sergeant Frank Holm of the Calgary Highlanders added in his diary: ‘When our bagpiper heard that the Germans were playing Christmas music, it struck a chord with him. The idea of opponents treating each other with humanity and camaraderie on Christmas. He grabbed his bagpipes and started playing. Unfortunately, the Germans apparently did not appreciate the wailing sound and fired mortar shells around him. The only thing that was hit was his pride as a musician.’

Some units of the Canadian The Toronto Scottish also celebrated Christmas at Groesbeek. On December 25, 1944, officers, as usual, served Christmas dinner to non-commissioned officers and enlisted men. The night before Christmas, the Canadians sang ‘Silent Night-Holy Night’ outdoors, and to everyone’s surprise, the Germans on the other side of the front started singing ‘Stille Nacht-Heilige Nacht’.

“Major Grant remarked that the Germans turned out to be better singers than the Canadians.”

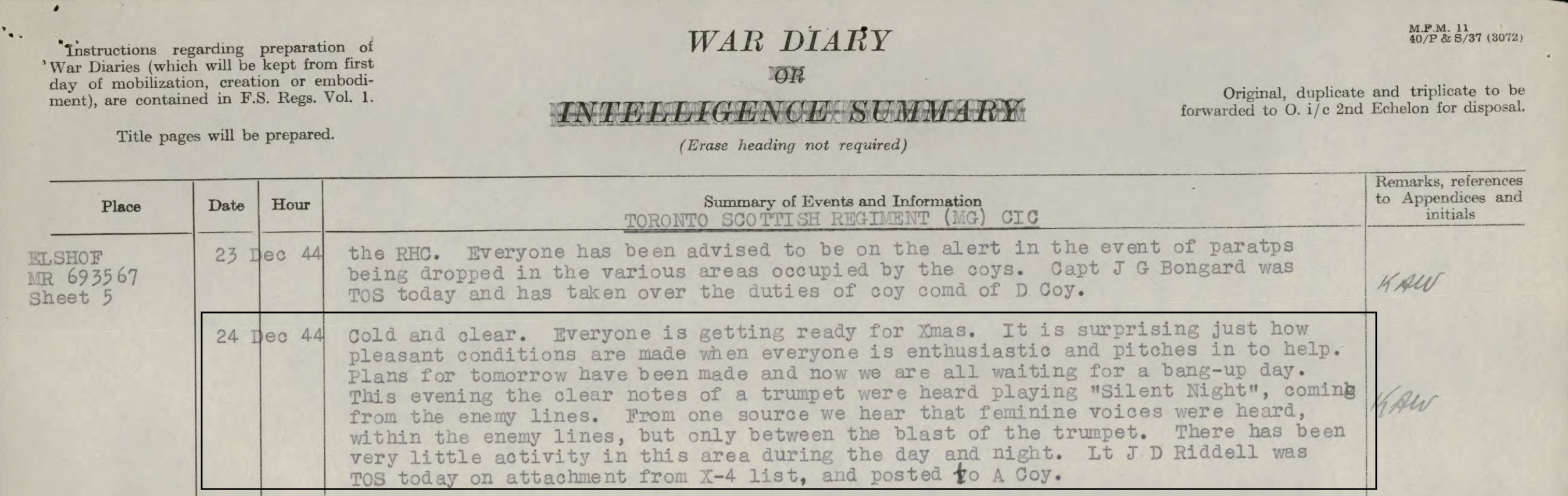

In the war diary of the Toronto Scottish, on December 24, 1944, there is a mention of the sound of a trumpet coming from the German lines. © Library and Archives Canada.

Amid the cold and silent night at the front in Groesbeek, the Régiment de la Chaudière disrupted the peace in an unconventional way on Christmas Eve. J. Armand, a member of the regiment, shared his experience of a remarkable episode where mortar shells and music formed an unexpected symphony. “On Christmas Eve, we were close to the Germans,” recalls J. Armand. “They weren’t patrolling, and we we

heard they were having a few drinks. At midnight, they played Christmas carols through a loudspeaker. In response, I decided to react with a few mortar shells, just to let them know we were still not friends.” However, the reaction to the mortar fire was as remarkable as unexpected. After the threatening sound of explosions, the Germans played ‘Lili Marleen,’ after which the music suddenly fell silent. Despite the tense situation, men on both sides of the front longed for home, resulting in a moment of shared humanity. “All our men were Catholic, and the chaplain walked with the communion from trench to trench,” J. Armand adds. This gesture of religious connection emphasized the universal need for comfort and hope, even in the grim reality of war.

At midnight, they played Christmas carols through a loudspeaker. In response, I decided to react with a few mortar shells, just to let them know we were still not friends.

Joe Pigott of the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry found himself in a foxhole near Groesbeek on Christmas night. He experienced it as follows: ‘The village of Groesbeek was southeast of Nijmegen. In Groesbeek, we literally faced the enemy on the other side of the street. I remember that it was particularly quiet on Christmas that year, both during the day and in the evening. We could hear the Germans singing and playing the accordion. But just before midnight, when it had become very quiet, one of the Canadian soldiers suddenly shouted, ‘Hitler is a son of a whore!’ For thirty seconds, there was a dead silence, then from the other side of the street came, ‘Just like Mackenzie King!’

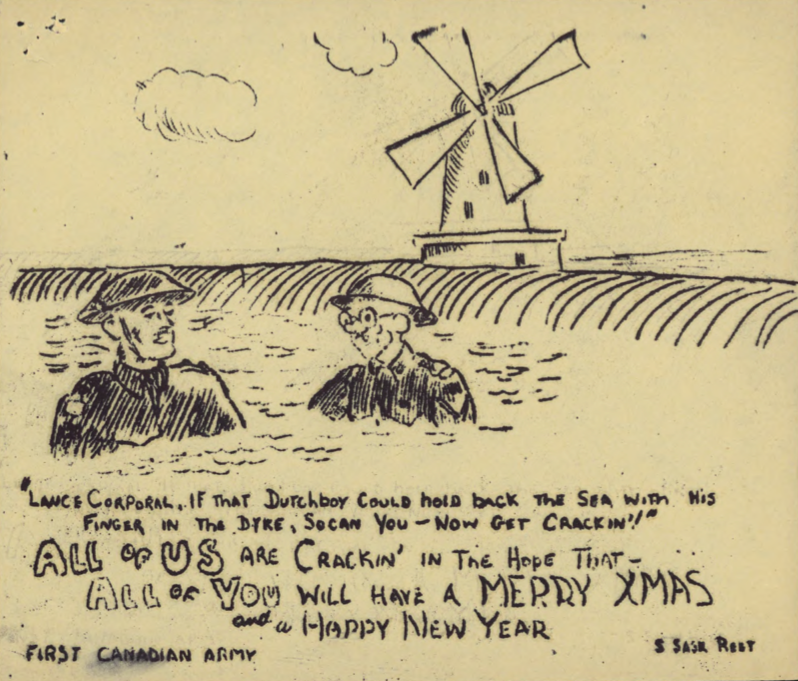

In the archives, several homemade Christmas cards have been found, created by Canadian soldiers from the South Saskatchewan Regiment stationed along the Maas River near Molenhoek. These cards bear witness to the determination and creativity of the soldiers amidst the hardships of war. © Library and Archives Canada.

A German Christmas gift

Ben Dunkelman of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada remembers the unique fireworks that the Germans offered as their ‘Christmas gift’: ‘I remember Christmas 1944 very well. We were in position overlooking plains along the Waal and a part of Germany, and the Germans were in heavily fortified positions opposite us. Because it was Christmas Eve, we felt relaxed. On the German side, a Christmas party was in progress; we could hear girls talking and singing, apparently having a lot of fun. It was contagious for my men, and they even started climbing out of the trenches, which was a bit too much for me. Just at that moment, the Germans began firing all kinds of tracer ammunition; it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. Much better than real fireworks. And then, without any warning, they unleashed a heavy barrage on our position. Thank goodness the men were already in cover. That was our Christmas gift from Hitler’s Nazi Germany.’

On the German side, a Christmas party was in progress; we could hear girls talking and singing, apparently having a lot of fun.

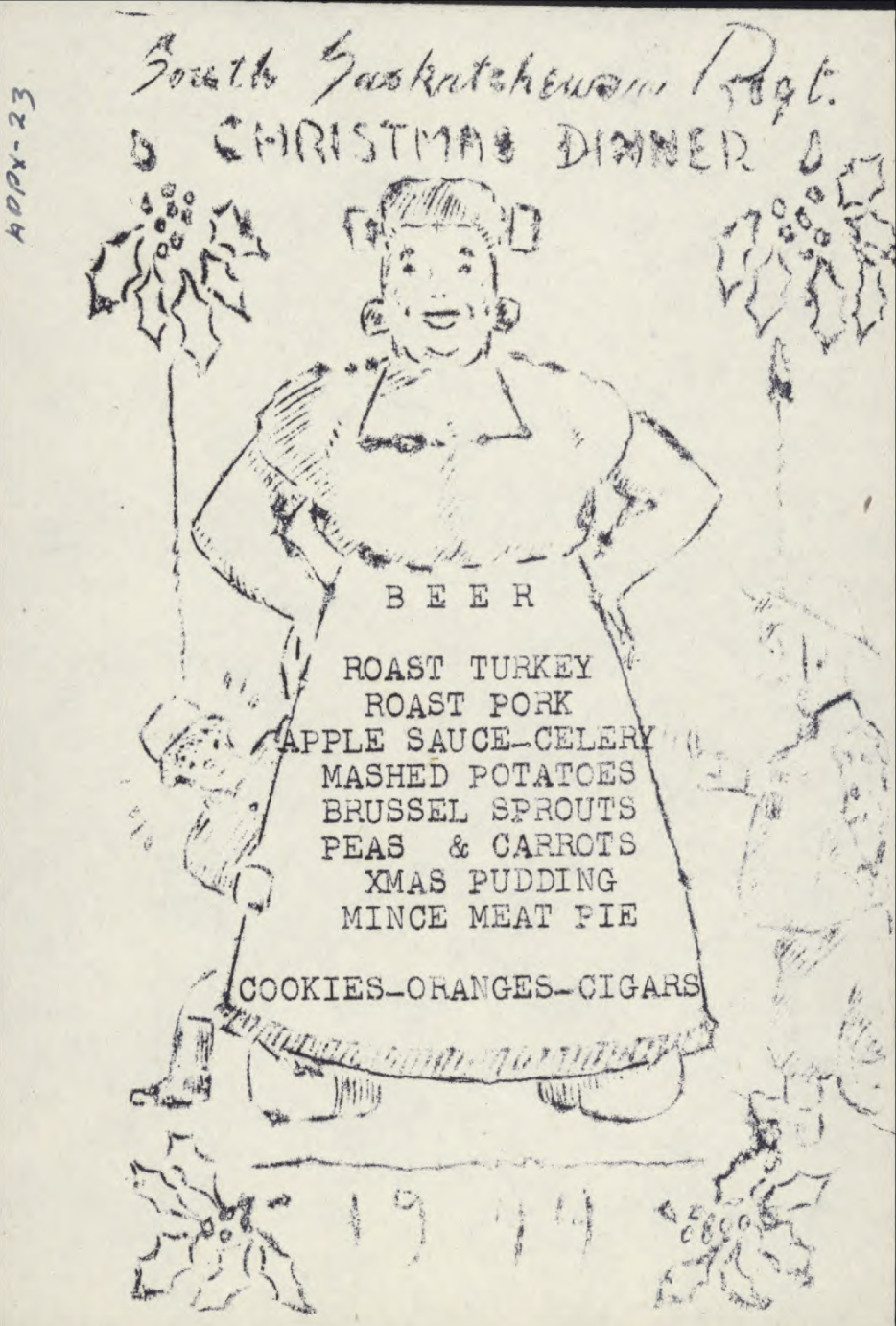

The Christmas menu of the South Saskatchewan Regiment on December 25, 1944. © Library and Archives Canada.

At the frontline of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders, a special celebration took place. While the winter air was crisp and the temperatures low, two companies made their way to Hotel de Groot for an unforgettable Christmas dinner. Amidst the freezing conditions, the chaplain, the colonel, and the brigadier spoke with the men. Each soldier enjoyed a bottle of beer before the Christmas dinner, and after the turkey was served, a four-member orchestra from the Novas took over. They played all the well-known Christmas songs, prompting those present to sing their hearts out. The joyful soldiers marched out of the hotel after the Christmas dinner, with the sun shining brightly and the ice along the dikes glistening. The air was infused with a fresh energy that gave the men a sense of movement and vitality. As the D Company marched back to their positions, their voices filled the air halfway to the trenches.

While the D Company marched back to their positions, their voices filled the air halfway to the trenches.

Canadian soldiers painting decorations on a canvas for the Christmas celebration in Nijmegen. © Library and Archives Canada.

Despite the threat of war, they, enveloped in the magic of Christmas, seemed to harbor no ill thoughts. Across the water, the Germans could hear the melodies of Christmas carols. Subsequently, the gentle tones of “Silent Night, Holy Night” filled the quiet night air, both in English and German. At that moment, the men on both sides of the front, albeit briefly, were united in celebrating the Christmas spirit. Upon arriving in the trenches, the men were surprised by an unexpected gift.

A flock of wild ducks landed in the marsh behind their positions, as if a gift from Santa himself. Corporal Pulsifer and his comrades, armed with Bren and Sten machine guns, decided to try their hand at duck hunting. However, their enthusiasm resulted in nineteen shot ducks, without a single meal to show for it. The men quickly realized that firing a salvo from a Bren machine gun left little of the duck meat; all that remained were feathers and bones on the water.

As the evening progressed and hunger struck again, an unexpected event unfolded. A goat in reasonable condition walked into a minefield in front of the positions of the 16 Platoon. The roasted goat that followed provided an unforgettable Christmas meal at the front, where the men felt connected by sharing this unique experience amidst the challenging conditions of war. Thus, Christmas on the frontline of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders became a memorable celebration of camaraderie, joy, and unexpected turns.

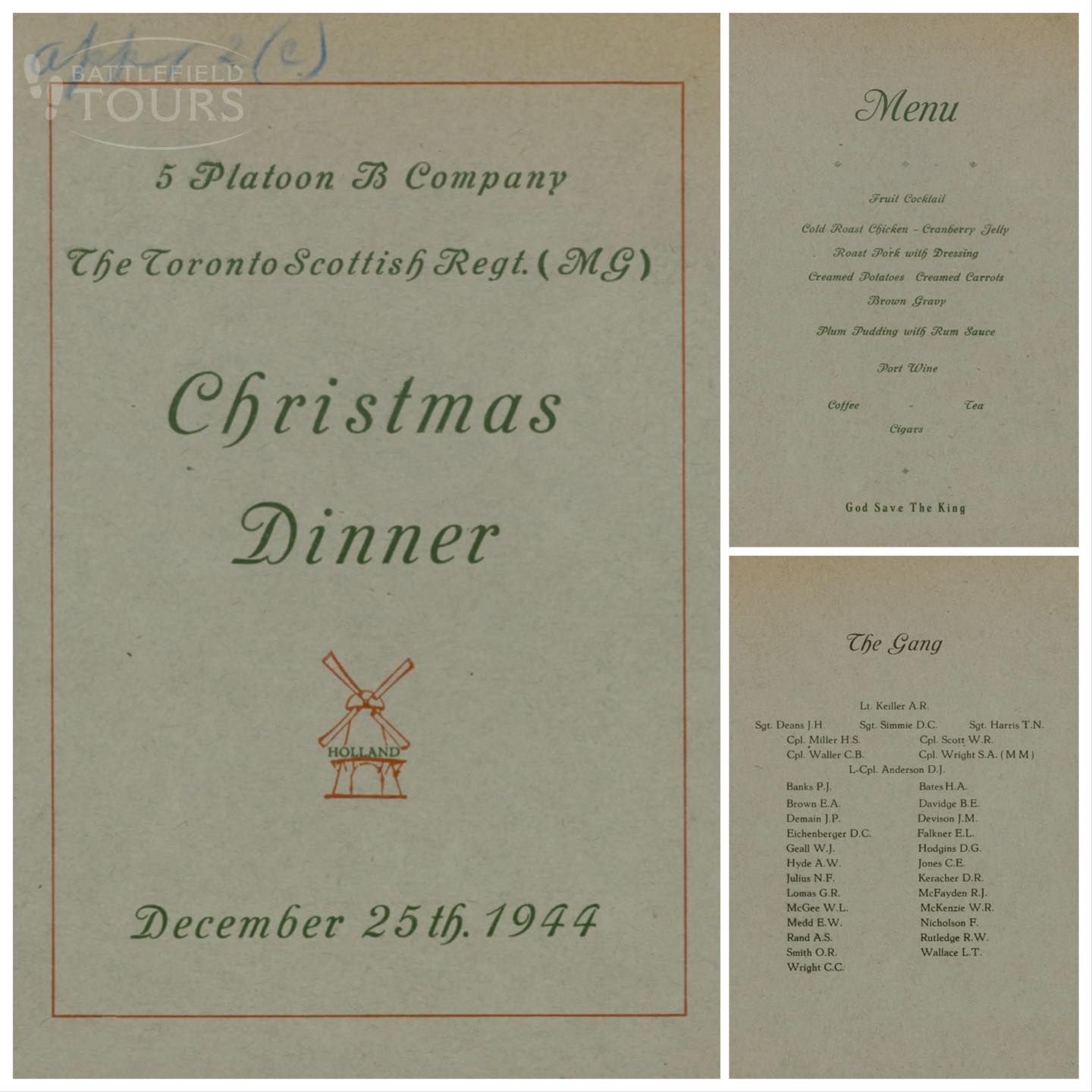

On December 25th, the Canadian officers and soldiers of 5 Platoon, B Company, Toronto Scottish Regiment (MG) were treated to their Christmas meal, followed by cigars as a festive conclusion! During this time, the Toronto Scottish were stationed at Landgoed Elshof near Malden, Netherlands. © Library and Archives Canada.

The Special Christmas Dinner

Doug Shaughnessy of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles was stationed with a welcoming Dutch family during the Christmas days. “While we were getting ready to pick up our Christmas dinner, they were sitting at their table for their own modest meal. Two pieces of bread, a bit of butter or cheese, and three or four people to share it – a scene that reflected the scarcity and hardships of that time. When we went to the mess hall for our own supper, the regiment had arranged a special Christmas dinner for us – with two bottles of beer, turkey, and various other treats specially brought in from Canada.

For me, and many others, this was one of the most memorable Christmases ever.

A Dutch boy holds a sign that reads “Christmas 1944, Allied Friends GOD BLESS YOU” during a Christmas dinner for Canadian soldiers in ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

After enjoying our own feast, we took a moment to clean our mess tins before returning to the frontline. We filled them again with turkey, potatoes, gravy, and other delicacies and brought it back to the Dutch family, a small act of gratitude for their hospitality. For me, and many others, this was one of the most memorable Christmases ever. Amid the hardships of war and the distance from home, we were warmed by the generosity of Dutch hospitality.

Christmas at the Maas

On Christmas Day, Major Tim Tedlie, commander of ‘C’ Squadron of the British Columbia Regiment, stood watchful on the banks of the Maas. His companions were his Sherman tank and a cold turkey leg, which he washed down with beer from a tin mug. His men had enjoyed an elaborate Christmas dinner a few hours earlier. Traditionally, the regiment, nicknamed the ‘Dukes,’ adhered to Canadian regimental traditions.

A Sherman command tank of the 13th-18th Hussars, 8th Armoured Brigade, near the Waal River at Nijmegen on October 15, 1944. © Imperial War Museum

The officers, including Tedlie himself, had first served the Christmas dinner for the lower ranks before starting their own meal. A peaceful scene that was abruptly disrupted when the regiment was immediately called to the front. Without hesitation, Tedlie and his officers headed to their tanks, hastily ladling their Christmas dinners into mess tins. Explosions were occasionally visible on the horizon, and the occasional sound of a machine gun cut through the air. The war was unmistakably ongoing, but immediate danger was not palpable everywhere.

The war was unmistakably ongoing, but immediate danger was not palpable everywhere.

Tedlie, although aware of the ongoing threat, did not see an immediate danger. Occasionally, grenades exploded on the riverbanks, and sometimes a trail of tracer ammunition illuminated the darkness. The war was a constant reality, but at that moment, there was no immediate threat. Yet, Tedlie knew that this could change in an instant. His keen awareness and leadership kept the squadron alert, ready to respond to any unexpected developments. Christmas by the Maas became a reminder of the unpredictability of the front, even at the most unlikely moments.

An unforgettable Christmas for Elshout

In an admirable act of generosity and solidarity, The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada regiment organized an unforgettable Christmas party for the children of Elshout on December 17, 1944. The festivities began with a captivating performance titled “The Three Bears,” where young and old came together to enjoy an enchanting show. The children’s enthusiasm was palpable, with smiling faces lighting up the hall. After the magical performance, the iconic Santa Claus entered the stage, greeted by excited cheers from the children. The War Diary of The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada regiment recorded in detail the ecstatic joy that this special encounter brought to the young revelers.

On December 17, 1944, children from Elshout participated in a Christmas celebration organized by the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada. © Library and Archives Canada.

The 1st Canadian Army in Europe receives the Christmas mail.